The objective of this series of posts is to collect some notes about the implementation details and usage of Flexbuffers using Kotlin Multiplatform, and reason about where FlexBuffers can be a good replacement for our good old schemaless champion JSON.

Since I’ve written the Java port as well, so it is a good opportunity to compare and see where Kotlin can make our life easier when compared to Java.

This is part one of a series of posts with a few more planned, and the library itself is not yet distributed over maven, but you can check out on google/flatbuffers. The API is still being ironed out and I hope those posts help attract feedback and suggestions to make the library better.

- Part I - What is Flexbuffers?

- Part II - Flexbuffers: Kotlin MPP implementation details.

- Part III - Flexbuffers Benchmarks: Kotlin vs Java.

- Part IV - Flexbuffers: Json support & Benchmarks

What is FlexBuffers?

The single sentence ad:

Flexbuffers is a binary, schemaless, no-parsing, zero-copy1, serialization format, that gives you a compact message to be read in-memory at incredible performance and low memory footprint.

That effectively means that Flexbuffers is a binary serialization format, where its representation in memory is the same as the representation on the wire. Therefore there is no need for parsing, you can access a particular field in a Map without the need to read all fields.

Let’s quickly go through some of the main characteristics and compare them with JSON, since it’s the current most popular serialization used these days.

Schemaless

Same as JSON, being a schemaless format means the messages are “self-described”. So at the cost of increased payload, we can figure out the structure of the data at runtime.

The available types are very similar to JSON’s and could be mapped the following way:

| FlexBuffers | JSON |

|---|---|

| Map | Object |

| Vector/TypedVector/Blob | Array |

| String | String |

| Int/UInt/Float | Number |

| Boolean | true/false |

| Null | Null |

For the purpose of this post, we say Map or Object interchangeably.

There are more types in FlexBuffers, such as “Indirect Int” and “Indirect Float” that can be used as a performance trick to make vectors or maps more compact. But for now, this is what is important to know in regards to the types.

Usually not exposed as public API, there is also the “type” Offset. Which is a “pointer” to be followed through. It is the basis of the non-primitive types and allows the data to be represented as a DAG granting interesting characteristics that we will discourse in other sections.

Compactness, Offset and Repetitions

As a binary format, it is expected the data to occupy a smaller space than text based equivalent representation, at least in general. Flexbuffers stores the scalar types (Int, Uint, Float, Double) in the smallest unsigned representation possible. That means

a 255 UByte would fit in 8 bits, and 65535 UShort would fit in 16 bits and so on. The width of the scalar is defined by its parent node, for example, A vector type would define the width of the children’s scalar.

Besides the reduction of the scalar values, it is possible to enable string reuse. This is a powerful feature that, once enabled, all unique String keys and values are written just once. All the subsequent repetitions are replaced by an “Offset” which basically works as a pointer on the buffer for that repeated key. For objects with a lot of repeated keys and values this is a massive improvement in size.

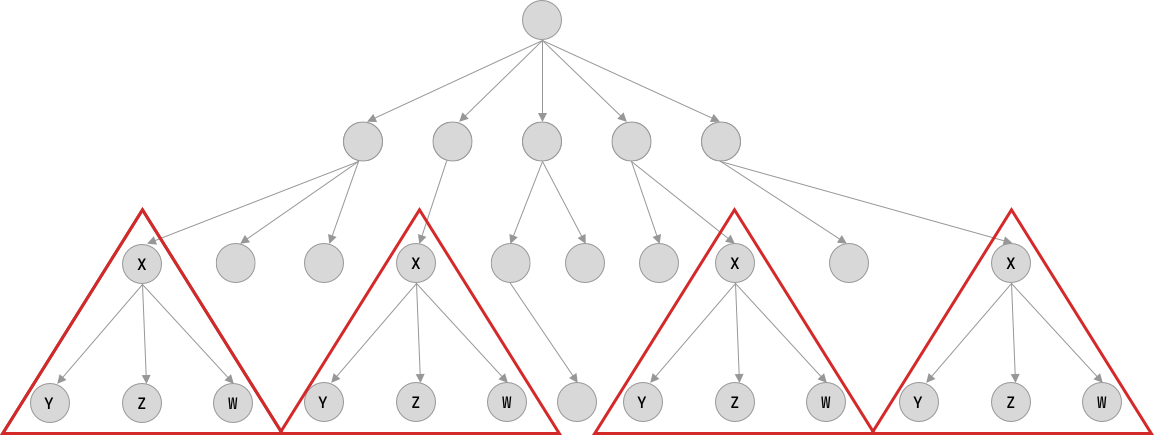

Another implication of the Offsets is the Maps and Vectors reuse. As said before, the data hierarchy on FlexBuffers might be seen as a DAG. But what if you have repeated branches in your data? Let’s say, you have several instances of an “object” that has exactly the same data. As seen on the image below:

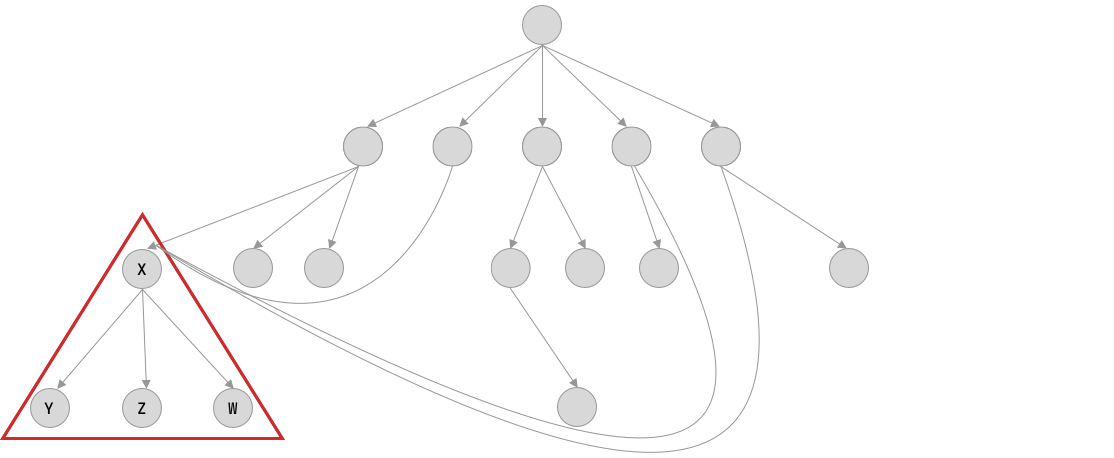

The serialization format allows replacing all repeated occurrences of those “branches” into an Offset, drastically reducing the space needed for the message. As you can see in the following illustration.

With all that said, you can see that in many cases the data in Flexbuffers ends up smaller than the JSON equivalent.

As an example, we can check the commonly used data benchmark twitter.json.It has approximately 617 KB in JSON and when converted to Flexbuffers becomes 255KB.

You can test yourself with different data by running the command:

flatc --binary --json --flexbuffers twitter.json

“No-Parsing”

Because you use the same representation of the data in wire, disk, or memory, there is nothing to be parsed. To fetch a field means following a set of Offset until you find the data requested. For example, you want to access:

//lets say the data is[10,20,30,40]

val ref = Flexbuffers.getRoot(data)

val myInt = ref[3].toInt()

In this example, an offset is read for getting the “head” of the vector. Since this is most likely a TypedVector the

offset for the third element is calculated based on the index (3) and then the number is read from memory. That would mean, most likely,

three memory accesses.

Vector has an additional read to fetch the element type.

Map works as two vectors, one for the keys, which are sorted, and one for the values. Accessing a key/value pair incurs a binary

search on the key vector, then access the value. You can also opt to access the value by position, assuming you know the order

in advance or have it cached.

“Zero-Copy”

That differs from JSON where the text-based representation on the wire is different from the in-memory representation, for example:

A JSON message would have looked like this:

{"myInt": 10, "myBoolean": false}

is represented on memory with something like:

val json = "{\"myInt\": 10, \"myBoolean\": false}"

val map = JSON.parse(json) // Could be any json parser library

map // A Map(JsonObject or any equivalent) is allocated

map["myInt"].asInt() // A Int object, possibly boxed

map["myString"].asString() // A String object, where "Hello world" was copyed/decoded

Flexbuffers avoid duplication by reading the data “at runtime” as the fields are requested. With one caveat: Strings.

Strings are immutable objects on Kotlin and there is no API to wrap a ByteArray as a String without a copy. So accessing a string

in Flexbuffers means decoding and copying the data into the String. Of course, the string can be cached and decode only once, but still a copy.

It would be possible to remedy this with a thin wrapper that implements a CharSequence, although this could be very efficient for ASCII strings, it would be very slow for UTF8 strings since it is not possible to predict where each codepoint starts and ends without walking throughout the whole data. So in a nutshell, if your data is dominated by unique strings and you perform full reads (e.g. read all fields), Flexbuffers would perform similar to any non-zero-copy protocol.

How it works?

In a nutshell, the user needs to be aware of only three classes: ArrayReadWriteBuffer, FlexBuffersBuilder, Reference.

ArrayReadWriteBuffer is just a ReadWriteBufferbacked by an internal ByteArray (okay, I lied and ended up introducing more concepts). ReadBuffer is

an interface that supports random access to a buffer and ReadWriteBuffer writes primitives, like Int, String etc on the buffer on little-endian. While instantiating

a new FlexBuffersBuilder you can pass an ArrayReadWriteBuffer to be used, or it will simply create one automatically for you.

FlexBuffersBuilder it is responsible for creating the data structure within the buffer and optionally do the string pooling for keys and values. Currently, they are in

separate pools, because the format for keys is different from the values. Keys are c-like 0 terminated strings and values store the length in bytes. Hopefully, in the future, a new KEY type can be introduced to unify the pools and save more space in the message. I could think of genuine cases where a key could also be present in value (query parameters for example).

Once the buffer is done, it can be read with Reference. There is a static function called getRoot(data: ReadBuffer): Reference that will return the reference to the root

of the data graph. From that, you can access any element of the data, as you can see in the example below.

// we create a builder and tell it to create string pool

val builder = FlexBuffersBuilder(shareFlag = SHARE_KEYS_AND_STRINGS)

builder.putVector { // adds a vector of variant types

put(10) // adds as integer

putMap { // adds a map / object

this["int"] = 10

this["hello"] = "world" // adds a key/value to map

this["float"] = 12.3

}

put("a string")

}

val buffer = builder.finish() // we tell we finished writing, now we can read

val root = getRoot(buffer)

println(root.toVector().size) // 3

println(root[0].toInt()) // 10

println(root[1]["hello"].toString()) // world

println(root[2].toString) // a string

Conclusion

Flexbuffers is a very interesting format with an uncommon interesting characteristic: It introduces “Pointers” and let the user access data indirectly through it. This creates a series of opportunities at the cost of potential additional memory access for reading fields.

This first part of a series of the post was meant to do a gentle introduction to Flexbuffers to make it easy to understand the internal details and reason about the decisions on the Kotlin Multiplatform implementation. In the next parts, we will dive a little bit more into the differences between Kotlin & Java implementation, and the advantages (and disadvantages) of Kotlin in comparison with Java.

Hopefully, some benchmarks will be present :P

-

Zero additional allocation is only possible on non-managed languages. ↩